In the Garden of the Mind

- Apr 28, 2017

- 6 min read

My memories are full of gardens. Not all of them are especially worthy; most are the dog-roses and pampas-grasses of urban parks. Other, rarer memories are of the fantastical gardens of my summer holidays, the Tolkienesque grandeur of mists roiling over swathes of tree ferns and giant rhubarb (taller than my dad!) at Heligan. Or there were the futuristic geodesic domes of the Eden Project, whose exotic orchids and rare plants did little to impress me, having grown up near a botanical garden, but whose excess did – its size, the industrial approach to growing, the waves of tiered walkways and misty tracks. Best of all, though, was my grandparents’ garden in the Highlands, a rising bank of peaty soil overlooked by fir-trees and with high fences to keep the deer out, where from the top of the potato patch you could see the whole length of the village and the sugar-loaf mountains climbing beyond. I was more concerned about what I could do in the garden than any view, and I gladly helped my Grannie prepare dinner by pulling handfuls of mange-tout or blackberries, from the bushes.

Both a profession and therapy, gardening is that rare thing which can turn a sour mood or fill an empty day with rewarding, if strenuous occupation. Our garden at home, an unwieldy strip of grass that runs on behind our house, broken intermittently by trampolines, vegetable patches, sheds, chicken coops and various experimental raised beds, is hardly up to the standards of those childhood reveries. There are beautiful parts to it, like the crab-apple blossom which turns the view out of my kitchen window into an explosion of heady-purple each April, but on the whole our work was too dilettantish to make a real garden of it, those places you step into and feel an air of mystery, or patient discovery, or calculated order. There was rarely any plan to it: you’d go out and do what needed doing. As a sometimes-moody teenager, what mattered was that it was my garden, into which I could go dig, remembering Kipling’s frustration poem:

The cure for this ill is not to sit still,

Or frowst with a book by the fire;

But to take a large hoe and a shovel also,

And dig till you gently perspire;

And then you will find that the sun and the wind,

And the Djinn of the Garden too,

Have lifted the hump—

The horrible hump—

The hump that is black and blue!

That time spent digging trenches or dead-heading roses is a British vocation, and we do it even when we are not frustrated (the one in three women who say they prefer gardening to sex aside, perhaps): we have our flower shows, we have our plant nurseries, we have Gardener’s Question Time. Simply spending time in a garden can feel like a cure-all – after a nasty break up I stayed up till dawn in mine, wrapped in a blanket and listening to the cooing of the collared doves in the holly tree. When dawn finally rose, I picked raspberries straight from the cane and went to bed more rested than any amount of self-reflection or talking to friends would have left me.

In the course of my degree I end up reading about gardens, but always at the service of some important allegory or meaning: Milton, Evelyn, Pope. The Sumerian epic Gilgamesh, our first extant work of literature, found gardens meaningful enough to put one at the end of the world, concealed on the other side of a tunnel of death. It is planted with trees of ruby and lapis lazuli bushes, enough to make even Gilgamesh, killer of Giants and seeker of eternal life, pause. Then there is Eden, which was free from Sin until our corruption drove us out of it; and who doesn’t long for that place like Milton’s Adam does. Joanna Newsom thought that the gift of Eden is its idea, dormant in all soil, of starting anew:

I found a little plot of land

In the Garden of Eden

It was dirt and dirt is all that same

I tilled it with my two hands

And I called it my very own;

There was no one to dispute my claim.

This is the garden that most appeals to me; a garden which calls you to dig into it, to see its constant state of work. As Eve says to Adam in Paradise Lost: ‘the work under our labor grows’. It can be found anywhere, and is open to anyone.

When I was young we used to climb up the zig-zag at Selbourne Hill in Hampshire, a track leading up the hill above the village which the naturalist Gilbert White had spent many years cutting out of the chalk of the South Downs. Gilbert White was one of Britain’s first naturalists; his The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne reflects a peaceful but intense interest in his sweet especial rural scene. In a series of letters, he presents his observations from years of life in that secluded part of Hampshire: his book is so English it even opens in iambic pentameter. The episode of the falling cobwebs is my favourite. Setting out one September morning, White and his dog were both forced to return home, blinded by a thick rain of gossamer.

The magnitude of the event was confirmed when the neighbouring villages of Alresford and Bradley report the phenomenon, so that ‘this wonderful shower extended in a sort of a triangle, the shortest of whose sides is about eight miles in extent.’ He postulated correctly, with no modern knowledge of atmospherics or biology, the cause: spiders weaving sky-sails from their silk. Whilst he is an expert observer, his total lack of the romantic association we have for flowers chimes with me. The charming sounding Helleborus foetidusappears the most interesting: ‘The good women give the leaves powdered to children troubled with worms.’ On the topic of earth-worms he is more effusive: earth-worms are almost a hobby-horse ‘perforating, and loosening the soil’, a vital foodstuff for ‘half the birds, and some quadrupeds’, ‘promoting of vegetation.’ We are told that ‘a good monography of this small and despicable link in the chain of nature would afford much entertainment and information.’ Others have followed in Gilbert White’s muddy footsteps: one of my favourites is Edith Holden’s The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady. Writing from the nearer side of the Romantics, she illustrates the year through its pastoral scenes with phenological illustrations of marsh-violets, foxgloves and sloes, adorned with topical quotations and short personal accounts. Reading her, time itself is part of the garden, an effect of the cycle of nature.

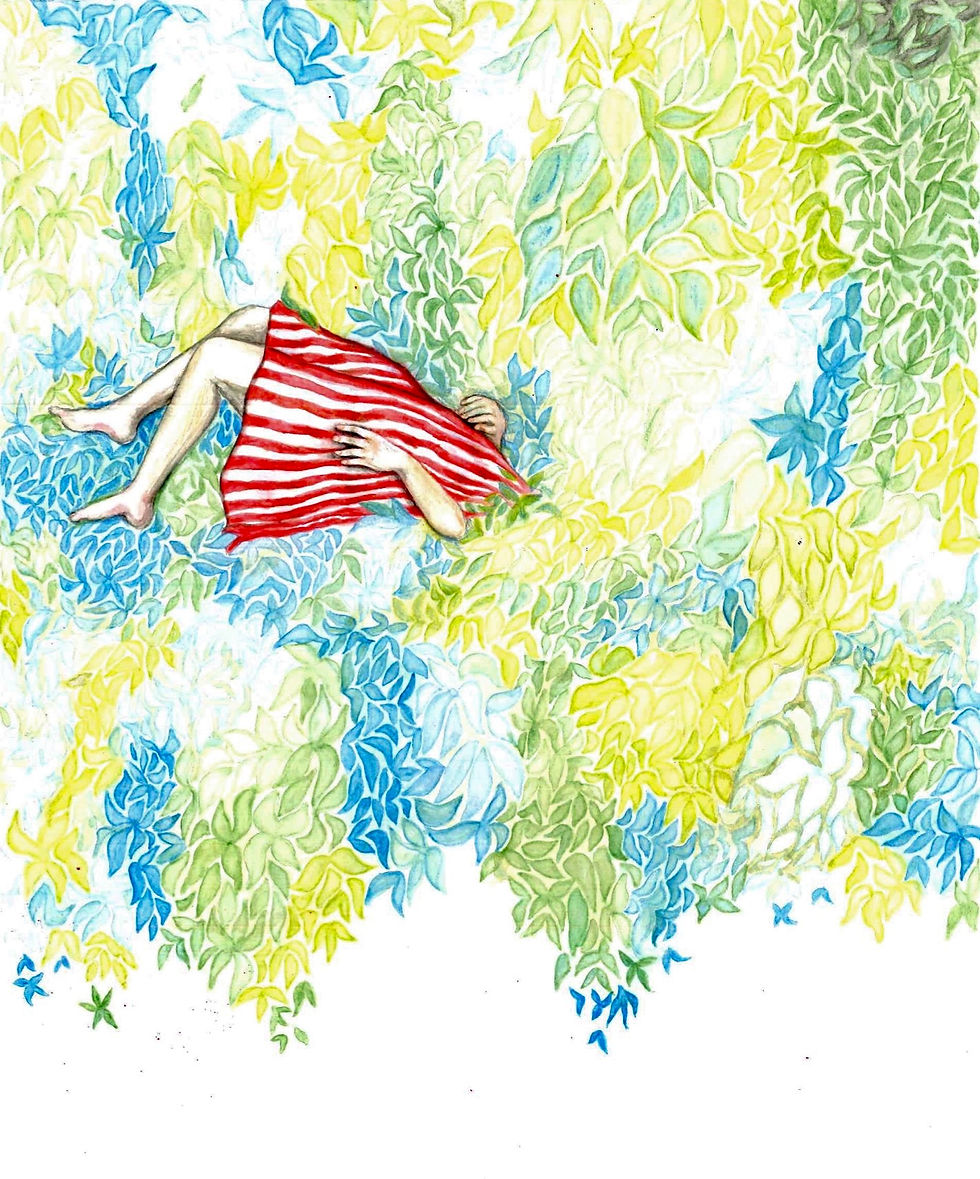

When I visit the local Botanical Gardens, or the misty valley gardens of Cornwall and Wales, or even step into the unruly strip from my back door, I am sometimes overwhelmed. The overwhelming is itself a relief, the permission to let my mind wander into imaginings of the germination of some small flower or the roots of the fennel, or like Holden to feel the explosive cycle of nature as it connects with my own sense of time. As a student I’ve been too busy to garden seriously, but at the back of my mind I always imagine parts of the plan I would make out one day: here a herb garden with sage, sorrel, marigolds and mint, there a great aspen tree to sit beneath. Perhaps it will be over a decade before I have a garden of my own – in the meantime I have the many gardens of the mind – the haunted, the ornate, the chaotic, and the quiet. In my finals I will probably write about Andrew Marvell’s Upon Appleton House. He reflects upon the earthly majesty of the house, its storied history, puritanical ethics and all the other sundries which will probably deserve dialectical unpicking. Like Marvell, though, I am more drawn to the gardens, where like an ‘easie Philosopher he may among the Birds and Trees confer’. Of course, such a retreat cannot be forever, but for those moments I relax as:

The mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness;

The mind, that ocean where each kind

Does straight its own resemblance find,

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green thought in a green shade.

Those moments where we withdraw into that green shade are rare, but the gardens of the western world remain resiliently open. In their enormous biological variety and complexity, I can be attentive like Gilbert White, or consoled, or charmed, or simply busy like Adam – pulling up that final patch of crabgrass.

PETER VICKERS

Peter Vickers reads English at Magdalen. He wishes he was on a Scottish island somewhere.

Comments