In Review: Susan Howe's Penitential Cries

- The Oxford Review of Books

- Dec 4, 2025

- 7 min read

By Adam Judah Krasnoff

A lifetime of reading yields strange ghosts. One of the late novels of David Markson (the first in the tetralogy often called The Notebook Quartet) is aptly titled Reader’s Block. Its narrator, a nameless Reader who has amassed an encyclopaedic quantity of abstruse references, quotations, biographical factoids, and assorted marginalia, is faced with a peculiar contradiction: his learning seems more obstructive than instructive. Is his memory faultless or hopelessly obscured?

The poetry of Susan Howe has for decades been animated by the act of reading as much as the act of writing. She is perhaps best known for two works of hybrid criticism—My Emily Dickinson, a book-length study of the American poet, and The Birth-Mark, an exploration of early American literature—which seem to answer for Wallace Stevens’s famous dictum that ‘poetry is the scholar’s art’. In both her criticism and her verse, Howe has challenged the limits of the archive, making the outer reaches of the American language her uneasy home territory. In a preface to Frame Structures, a volume of her selected early poems, Howe returned to her childhood in Buffalo, New York and Cambridge, Massachusetts. In a series of cascading prose poems, she shifts between historical detail and the indeterminacy of childhood remembrance. ‘In those early days language was always changing’, Howe writes. ‘Faded words fell like dead leaves in a closed circle moving toward the mind but we didn’t know we were born because deep down there is no history.’ Does this qualify as an admittance? No history for whom? As Howe accumulates archival material, the history of her birthplace becomes clearer, while her personal history grows increasingly murky. This preface seems a harsh kind of argument: facts, correctly sequenced, affirm what even the most vividly recollected scenes from memory deny.

Now Howe, at the age of 88, is in ‘the evening of life’. Speaking of her new work, Penitential Cries, out this September from New Directions, she quotes Sir Thomas Wyatt’s sonnet: ‘My galley, chargèd with forgetfulness, / Thorough sharp seas in winter nights doth pass…’ One might easily place Wyatt’s poem in counterpoint to a famous lyric by Dickinson, still perhaps Howe’s central pole of reference:

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul –

Wyatt’s galley and Dickinson’s frigate posit differential relations to memory and reading; the vessels (and the poems in which we find them) are, in miniature, what the critic Paul de Man called ‘allegories of reading’. Dickinson makes her allegory literal; the ‘Book’ is invoked in the first line. In her poem, the frigate is a form of reassurance; the book, our frugal chariot, carries us safely through treacherous waters, edifying and securing us. Wyatt, meanwhile, remains more obscure. Ought we to take his windswept galley for an analogue of the self—the ‘I’, appearing at last in the poem’s final line? I take Wyatt’s sonnet as a depiction of an aged mind (‘chargèd with forgetfulness’) confronted with the problem of legibility, the difficult-to-impossible task of reading its surroundings.

The same could be said of Howe’s latest collection. It is a late work deeply concerned with its own lateness, a sort of pre-requiem for her own death. The final pages form a moving epitaph for her sister, the great poet and novelist Fanny Howe, who died this July. Penitential Cries, more than any previous collection by Howe, is a work of retrospection, a survey of a writing and reading life from a poet teetering on the edge of that most peculiar abyss, the loss of memory. ‘Tacking against the winds of time I can only cut and quote’, she writes. The collection is studded with moments like this, when Howe steps outside the poem to comment on its processes of composition. (Elsewhere, in a similar vein: ‘I’m sifting for sterling particles, delight of the hunt.’) As we read these halting poems, we are shuttled along from sterling particle to sterling particle, collecting on our way fragments of speech, lines of poetry both directly quoted and unattributed, and memories gauzed over by ‘the winds of time’.

But Howe can do a great deal more than cut and quote. While she has garnered a reputation as a collagist, synthesising found texts into literary patchworks, her lyric abilities have gone, if not unnoticed, then certainly underappreciated. Like other poets whose work skirts the academic, the theoretical, or the critical (Charles Olson, for example), much is made of the difficulty of Howe’s work, its abstraction and obscurantism. But when I read Howe, I am struck most by her willingness to cut through the vagaries of the figurative to uncover the frantic stuff of experience; its look, feel, and shape, its itness. The effect is achieved, in part, by the collocation of wildly different forms of language. So it is with ‘Penitential Cries’, the long poem which opens this new collection. Here we find psalmic quotations rubbing up against lines of unexpected intimacy: ‘So much happiness in the little word “clasp”’. There is no I here; Howe is neither confessing nor recollecting, per se. Yet the sound of the line, its gentle issuing of sibilants (so, happiness, clasp), seem to draw us in, to open an interior space, if only for a moment.

Another of Howe’s techniques involves slipping from single, broken lines to sections of prose poetry, from fragmentation to something approximating linear narration. This alternation plays out in the poem like a shifting of tenses: whereas the single lines take place in a timeless then, rather like the open field of memory, the prosaic sections bring us to the present, viewed in first-person, by and through Howe.

If there is a central, present-tense event in the poem, it is Howe’s visit to Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library, her ‘first post-Pandemic drive on I-95’. The library, with its labyrinthine corridors (six miles of shelves, Howe tells us), and its secret bounties of text, becomes both a metaphorical analogue for Howe’s thinking—she calls it ‘the dark republic of mind and spirit’—and a literal manifestation of the limits of her knowledge. One might well think of Borges’s Library of Babel, with its network of galleries and passages, ‘unlimited and cyclical’, wherein a Reader, after centuries spent wandering, begins to notice a recurrent pattern of books on its shelves, a hidden order. As we move through Howe’s long poem, we sense the recurrence of intertexts (Donne, H.D., Cocteau’s Orphée, the French mystic Marguerite Porete) alongside images from childhood—the Connecticut River, a window in Boston’s Massachusetts Memorial Hospital, her mother and father. It becomes clear that Howe, in her old age, will not be able to traverse her library for long enough to discern an order from these many disparate pieces. An eerie sense of entropy pervades the poem’s final pages—something seems to be unraveling.

The middle section of the book is dedicated to a sequence of Howe’s word-collages, titled ‘Sterling Park in the Dark’. These miniature concrete poems are composed solely of found text arranged in dense clusters, such that it is difficult to discern both their original source and exact contents. Howe has developed a meticulous process for constructing her collages, taking pages of source texts before cutting and pasting them together, preserving both the diverse, original typefaces of the found texts and the shapes of the lines she has decided to use. This form is nothing new for Howe; in fact, she exhibited a series of these word-collages at the Whitney Biennial in 2014. But they take on a new meaning in Penitential Cries. In effect, they are a method of imaging the phenomenon Markson called reader’s block—an immersion in text which yields not higher understanding, but vertigo, indeterminacy, a sense of loss.

How to ‘read’ these collages? Can they be read? It would be simple enough to let the jumbled words flow by. I imagine some readers might simply turn away from them at once, seeking the comfort of lineated poetry, a logical succession from word to word. But Howe has never offered her readers those comforts. Her word-collages are simply another means of defamiliarising a rapid montage of ideas, images, and quotations, condensed and elaborated. For me, the effect of the word-collages is rather like that of the shadow-boxes of Joseph Cornell, who gathered everyday objects sourced from thrift stores, yard sales, curbs and dumpsters, and combined them into surreal compositions drawn from dream-images and the fantastic effects of vaudeville and the early cinema. At a glance, Cornell’s boxes can look like mere detritus; closely examined, they reveal the most delicate patterns of arrangement. Likewise, Howe’s collages are full of strange doublings, rhymes, and haunting turns of phrase: ‘The moist poison in his heart he lanced’; ‘I can hear little voices whispering’; ‘It is very late in the evening in the big dusky library of this institution.’

The book ends with ‘The Deserted Shelf’, a much shorter poem than the titular one but similar in its construction, and ‘Chipping Sparrow’, the aforementioned elegy for her sister Fanny. In the former, we find the intertextual appearance of another poem recording a journey by sea, albeit a metaphorical one: Hart Crane’s ‘Voyages’. Howe quotes the final stanza of Crane’s tempestuous love-lyric:

The imaged Word, it is, that holds

Hushed willows anchored in its glow.

It is the unbetrayable reply

Whose accent no farewell can know.

By this point in the collection, Howe has quoted dozens of poems, both obscure and well-known; Crane might well be another star in the book’s growing constellation of reference. But unlike those others, Howe chooses to comment with striking directness on Crane’s lines: ‘This stanza is a definition of what every single line in a poem is bound to promise.’ For all the book’s uneasy flitting between states, its subtle conveyance of the loss of memory, its fraught and frantic relationship to histories both national and personal, there is real comfort in Howe’s affirmation of the power of Crane’s work. That power is palliative, if not truly curative. The ‘imaged Word’—frugal chariot—has kept Howe afloat. Is this the worth, in miniature, of a reading life: the solace of a few words, the right words, called to mind at the right time, when one is tossed on frantic seas, despairing of the port, as Wyatt put it? There are larger but few nobler purposes.

After the dense, allusive, fractured whole of Penitential Cries, ‘Chipping Sparrow’, with its succession of koan-like couplets, is a welcome relief in its forthrightness. It is a death-poem spoken in hushed, delicate tones, like a lullaby. Howe writes:

Quietness and calm

Rest and rejoice

No more doubt

Astonishing!

In her elegy we might well hear the childlike rhymes and refrains of the two sisters, Susan and Fanny, growing up together in Cambridge, plodding through snow and ice, just steps from Harvard’s Houghton Library. How much more daunting must those corridors of shelves have looked to a child—their silence, their stillness, their seeming impenetrability, waiting to be broken by a curious hand.

ADAM JUDAH KRASNOFF is a writer living in New York.

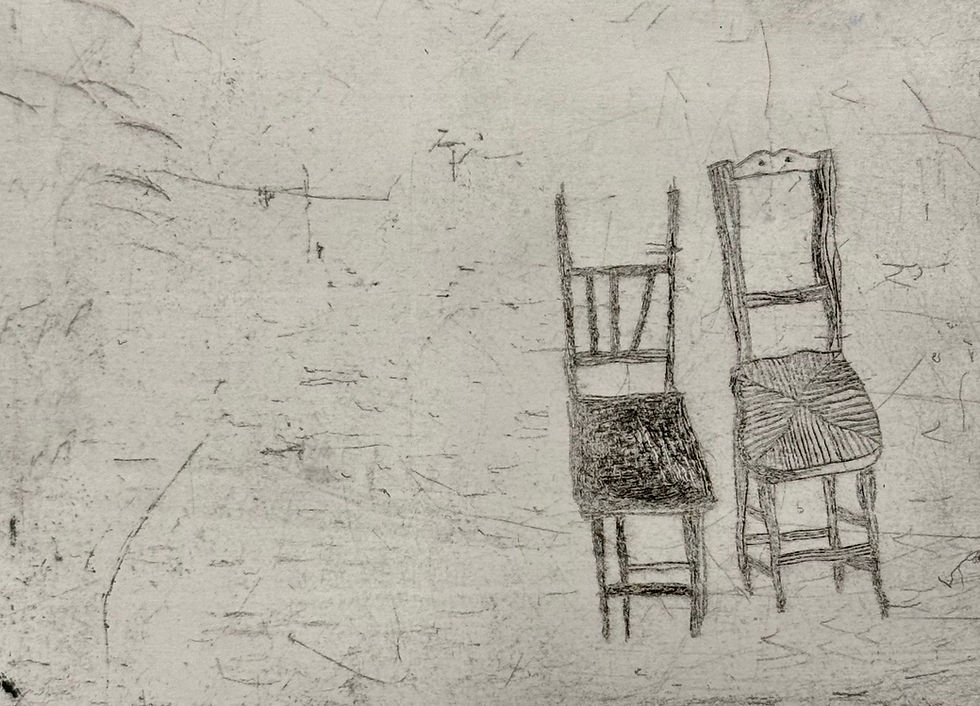

Art by Elizabeth Stevens

This review basketball legends feels like switching from an intense arcade game to a quiet reading mode where memory and emotion slow everything down. Susan Howe’s poetry reminds me of pausing a favorite game and thinking deeply about time, loss, and what stays with us after the screen fades away.

In Build Now GG, I trapped someone in a box and then forgot to edit my way in. We just stared at each other through the wall like confused NPCs.